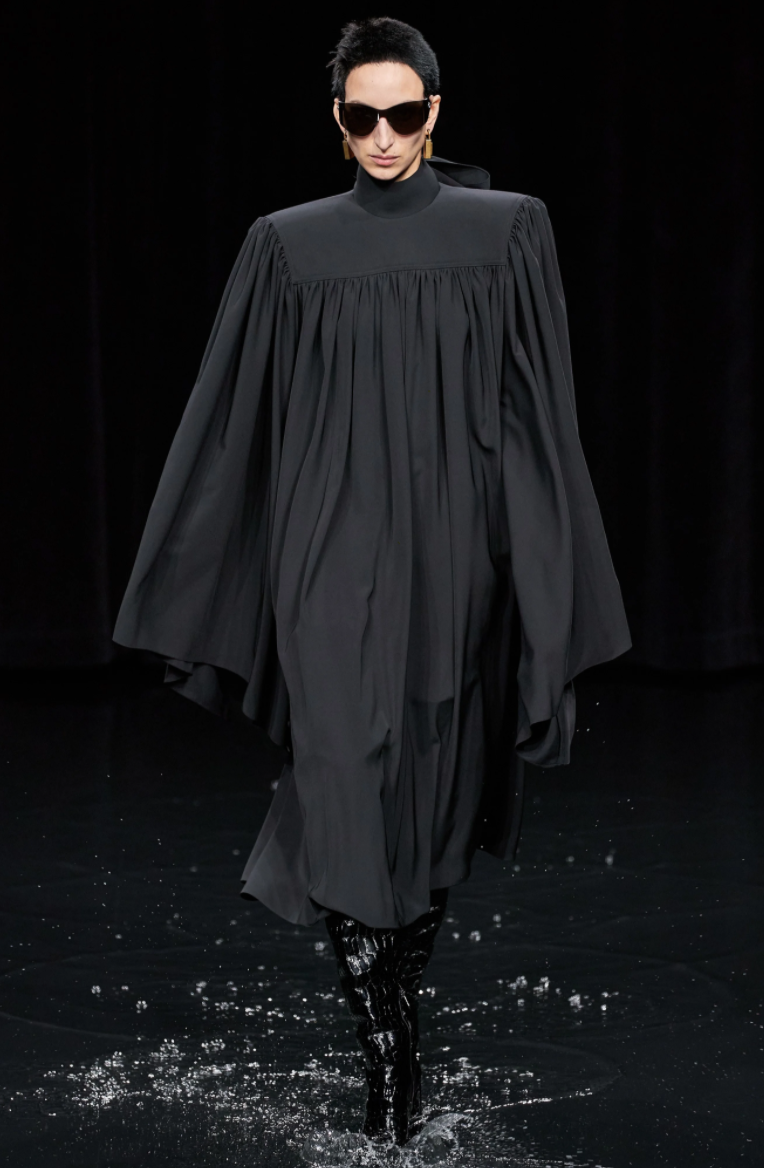

Louis Vuitton Fall 2020 Ready-To-Wear

/“I wanted to imagine what could happen if the past could look at us.”

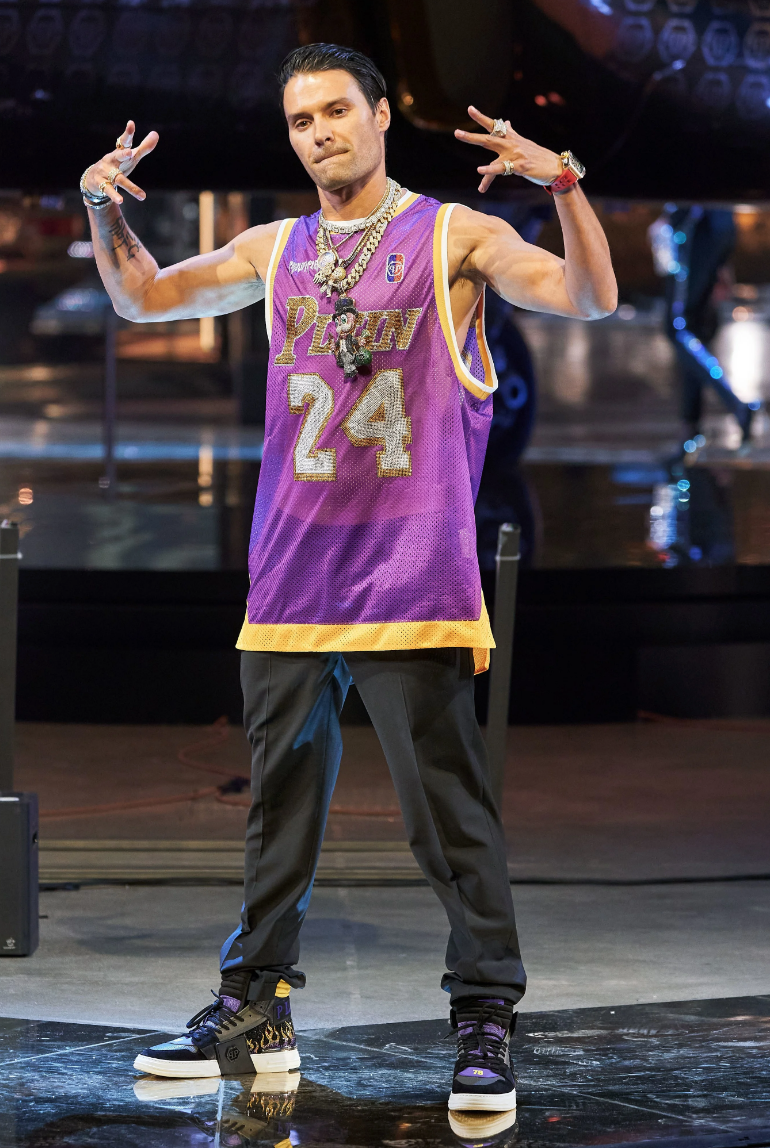

Nicolas Ghesquière is the cohost of this May’s Met gala (since then cancelled) and Louis Vuitton is sponsoring the Costume Institute exhibition, “About Time: Fashion and Duration,” that the gala celebrates. Ghesquière took as his subject this season the exhibition’s theme: that fashion is a mirror of the present moment—but not any old mirror. At Ghesquière’s Louis Vuitton, it’s a funhouse mirror in which eras, attitudes, and flashbacks intersect. And voilà: we flash forward.

This season Ghesquière enlisted the costume designer Milena Canonero, a frequent collaborator of Stanley Kubrick’s, to create a monumental backdrop of 200 choral singers, each one clothed in historical garb dating from the 15th century to 1950. It was a mammoth undertaking, and quite beautiful. “I wanted a group of characters that represent different countries, different cultures, different times,” Ghesquière explained beforehand. “I love this interaction between the people seated in the audience, the girls walking, and the past looking at them—these three visions mixed together.” The time-collapsing sensation was heightened by the fact that the song the chorus performed was a composition by Woodkid and Bryce Dessner based on the work of Nicolas de Grigny, a contemporary of Bach’s who never found fame.

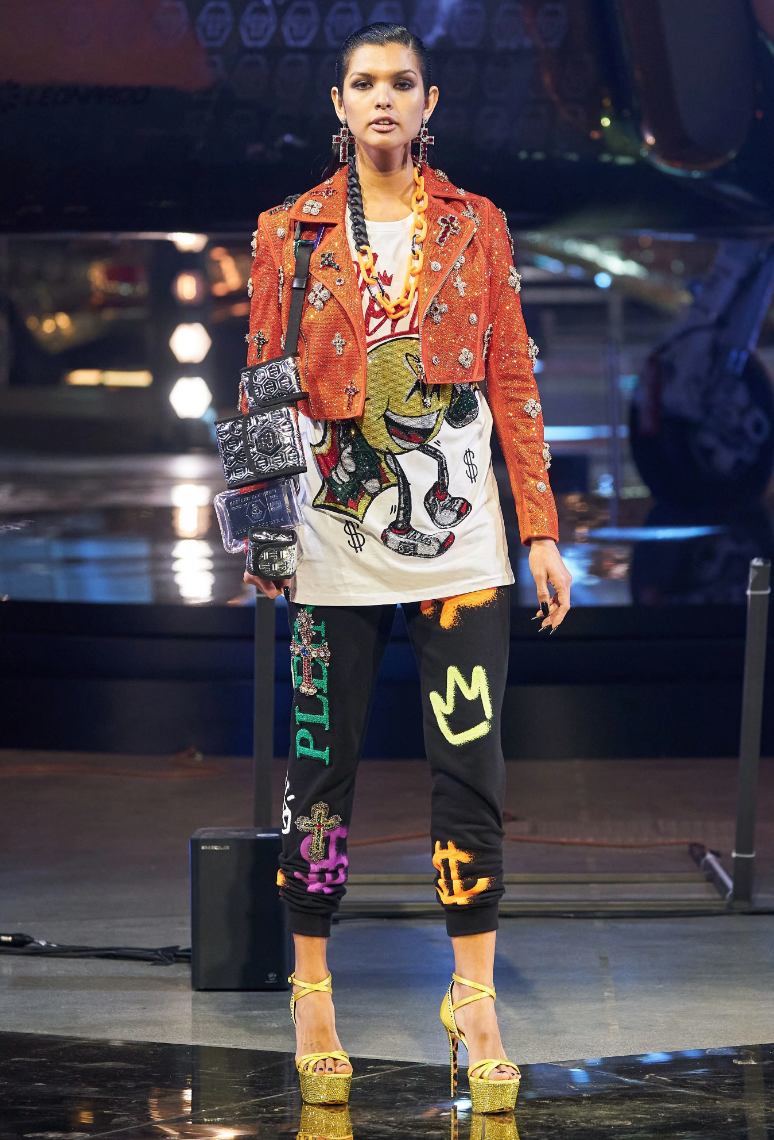

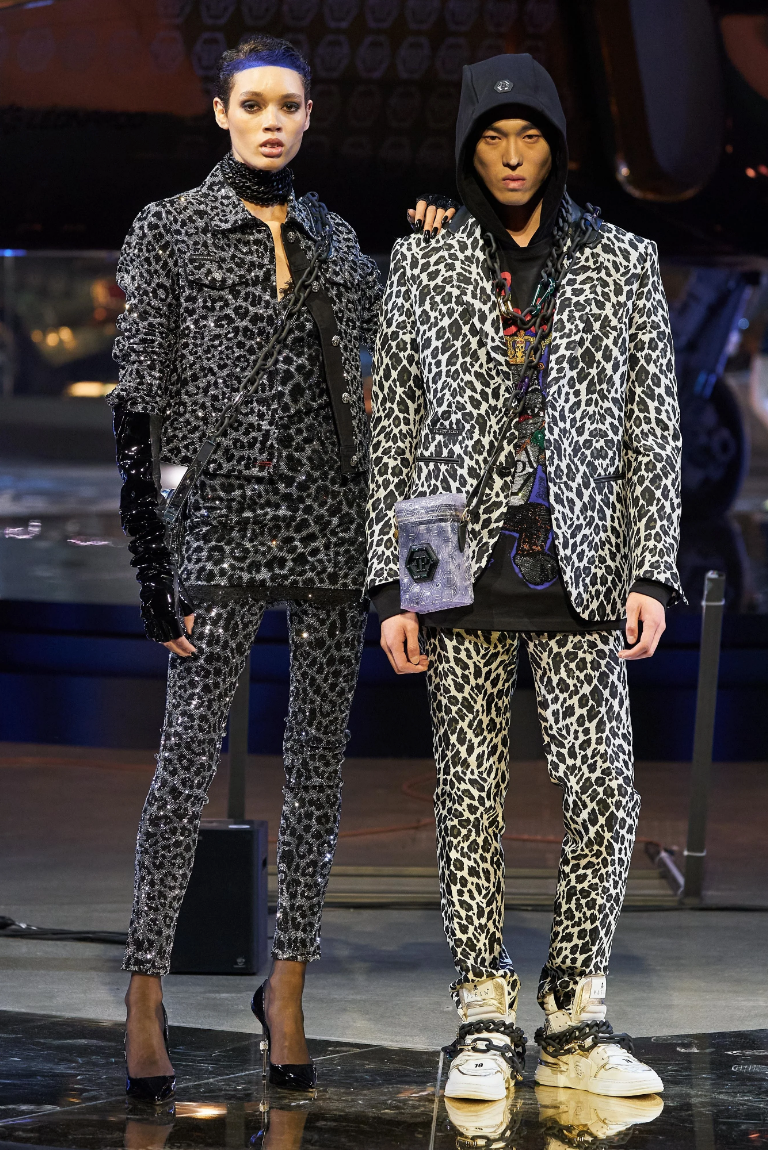

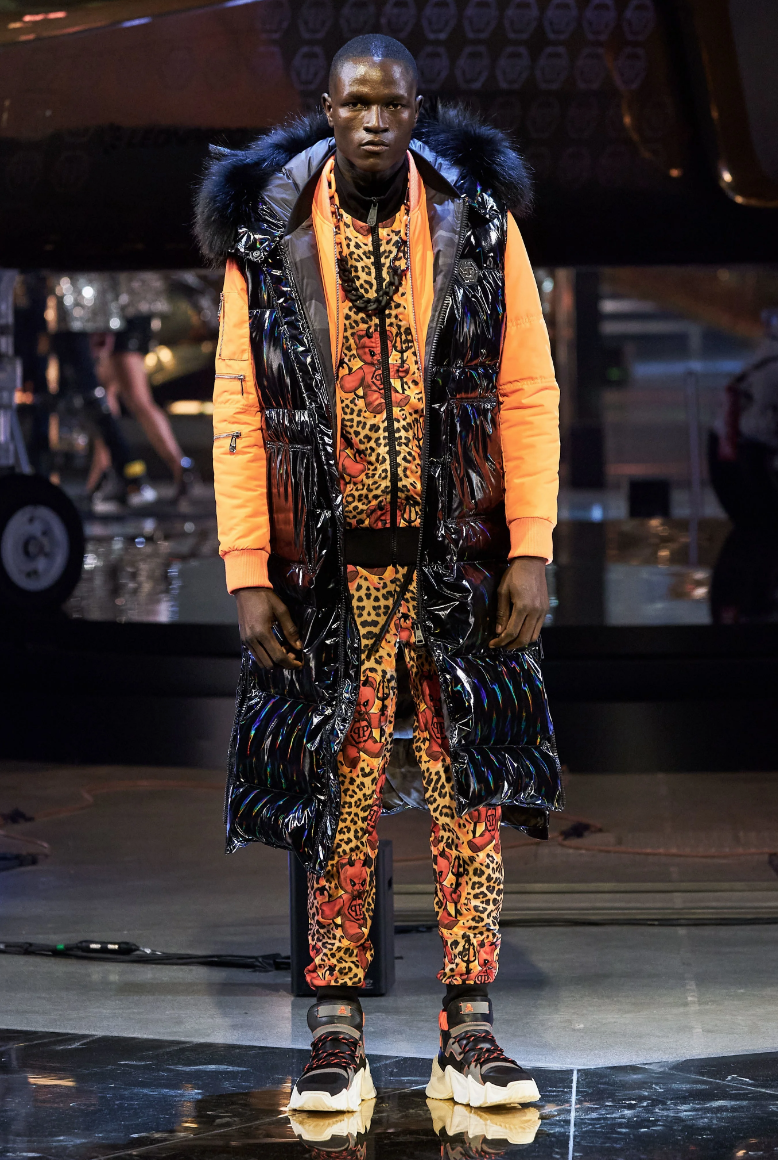

Arguably, all of fashion is a synthesis of the past, but Ghesquière makes a closer study of it than most. He’s compelled by the anachronous. For spring 2018, he clashed 18th-century frock coats and the high-tech trainers of our contemporary period. Here, there was more in play: jewel-encrusted boleros met parachute pants, buoyant petticoats were paired with fitted tops whose designs looked cribbed from robotics, and bourgeois tailoring was layered over sports jerseys. Ghesquière seemed particularly taken with the visual codes of distance and speed—be it race-car driving, motocross, or space travel.

The biggest jolts came from the collection’s sporty parkas, because they tapped into the language of the street. Seventy years from now, or 600, in a tableau vivant of fashion, the early 21st century will be represented by these signifiers of our collective preference for the comforts and ease of performance wear. Ghesquière has long been applauded for his sci-fi projections into the unknown, but he’s just as resonant when he’s locked into the here and now.

We asked him what his hopes are for the future. “What I want is everyone to be safe,” he said. “This world can become a little more serene, that’s what I wish.”

Source: Vogue

FASHIONADO